Security Cryptography

2019’s ./missing-lectures security and privacy lecture focused on how you can be more secure as a computer user. This guide builds on it and will focus on security and cryptography concepts that are relevant in understanding tools covered earlier, such as the use of hash functions in Git or key derivation functions and symmetric/asymmetric cryptosystems in SSH.

This guide is not a substitute for a more rigorous and complete course on computer systems security (6.858) or cryptography (6.857 and 6.875) from MIT. Don’t do security work without formal training in security. Unless you’re an expert, don’t roll your own crypto. The same principle applies to systems security.

This guide has a very informal (but we think practical) treatment of basic cryptography concepts. This guide won’t be enough to teach you how to design secure systems or cryptographic protocols, but we hope it will be enough to give you a general understanding of the programs and protocols you already use.

Entropy

Entropy is a measure of randomness. This is useful, for example, when determining the strength of a password.

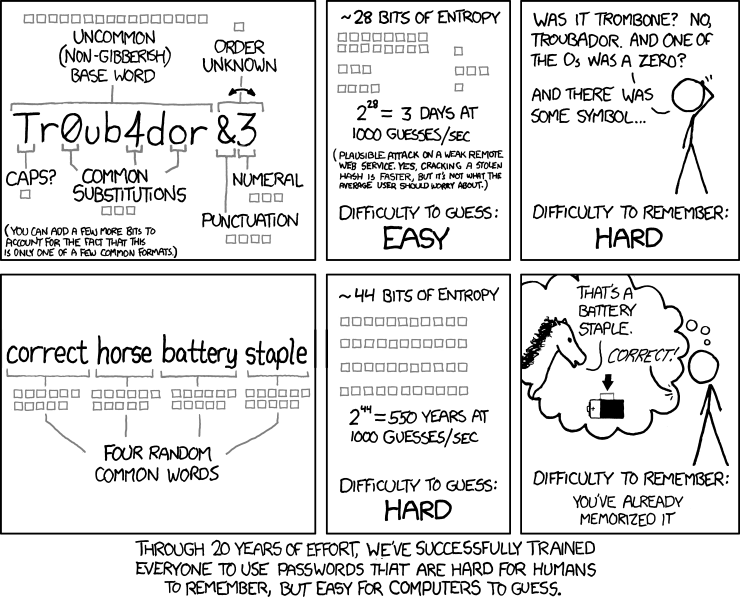

As the above XKCD comic illustrates, a password like “correcthorsebatterystaple” is more secure than one like “Tr0ub4dor&3”. But how do you quantify something like this?

Entropy is measured in bits, and when selecting uniformly at random from a

set of possible outcomes, the entropy is equal to log_2(# of possibilities).

A fair coin flip gives 1 bit of entropy. A dice roll (of a 6-sided die) has

~2.58 bits of entropy.

You should consider that the attacker knows the model of the password, but not the randomness (e.g. from dice rolls) used to select a particular password.

How many bits of entropy is enough? It depends on your threat model. For online guessing, as the XKCD comic points out, ~40 bits of entropy is pretty good. To be resistant to offline guessing, a stronger password would be necessary (e.g. 80 bits, or more).

Hash functions

A cryptographic hash function maps data of arbitrary size to a fixed size, and has some special properties. A rough specification of a hash function is as follows:

hash(value: array<byte>) -> vector<byte, N> (for some fixed N)

An example of a hash function is SHA1,

which is used in Git. It maps arbitrary-sized inputs to 160-bit outputs (which

can be represented as 40 hexadecimal characters). We can try out the SHA1 hash

on an input using the sha1sum command:

$ printf 'hello' | sha1sum

aaf4c61ddcc5e8a2dabede0f3b482cd9aea9434d

$ printf 'hello' | sha1sum

aaf4c61ddcc5e8a2dabede0f3b482cd9aea9434d

$ printf 'Hello' | sha1sum

f7ff9e8b7bb2e09b70935a5d785e0cc5d9d0abf0

At a high level, a hash function can be thought of as a hard-to-invert random-looking (but deterministic) function (and this is the ideal model of a hash function). A hash function has the following properties:

- Deterministic: the same input always generates the same output.

- Non-invertible: it is hard to find an input

msuch thathash(m) = hfor some desired outputh. - Target collision resistant: given an input

m_1, it’s hard to find a different inputm_2such thathash(m_1) = hash(m_2). - Collision resistant: it’s hard to find two inputs

m_1andm_2such thathash(m_1) = hash(m_2)(note that this is a strictly stronger property than target collision resistance).

Note: while it may work for certain purposes, SHA-1 is no longer considered a strong cryptographic hash function. You might find this table of lifetimes of cryptographic hash functions interesting. However, note that recommending specific hash functions is beyond the scope of this lecture. If you are doing work where this matters, you need formal training in security/cryptography.

Applications

- Git, for content-addressed storage. The idea of a hash function is a more general concept (there are non-cryptographic hash functions). Why does Git use a cryptographic hash function?

- A short summary of the contents of a file. Software can often be downloaded from (potentially less trustworthy) mirrors, e.g. Linux ISOs, and it would be nice to not have to trust them. The official sites usually post hashes alongside the download links (that point to third-party mirrors), so that the hash can be checked after downloading a file.

- Commitment schemes.

Suppose you want to commit to a particular value, but reveal the value itself

later. For example, I want to do a fair coin toss “in my head”, without a

trusted shared coin that two parties can see. I could choose a value

r = random(), and then shareh = sha256(r). Then, you could call heads or tails (we’ll agree that evenrmeans heads, and oddrmeans tails). After you call, I can reveal my valuer, and you can confirm that I haven’t cheated by checkingsha256(r)matches the hash I shared earlier.

Key derivation functions

A related concept to cryptographic hashes, key derivation functions (KDFs) are used for a number of applications, including producing fixed-length output for use as keys in other cryptographic algorithms. Usually, KDFs are deliberately slow, in order to slow down offline brute-force attacks.

Applications

- Producing keys from passphrases for use in other cryptographic algorithms (e.g. symmetric cryptography, see below).

- Storing login credentials. Storing plaintext passwords is bad; the right

approach is to generate and store a random

salt

salt = random()for each user, storeKDF(password + salt), and verify login attempts by re-computing the KDF given the entered password and the stored salt.

Symmetric cryptography

Hiding message contents is probably the first concept you think about when you think about cryptography. Symmetric cryptography accomplishes this with the following set of functionality:

keygen() -> key (this function is randomized)

encrypt(plaintext: array<byte>, key) -> array<byte> (the ciphertext)

decrypt(ciphertext: array<byte>, key) -> array<byte> (the plaintext)

The encrypt function has the property that given the output (ciphertext), it’s

hard to determine the input (plaintext) without the key. The decrypt function

has the obvious correctness property, that decrypt(encrypt(m, k), k) = m.

An example of a symmetric cryptosystem in wide use today is AES.

Applications

- Encrypting files for storage in an untrusted cloud service. This can be

combined with KDFs, so you can encrypt a file with a passphrase. Generate

key = KDF(passphrase), and then storeencrypt(file, key).

Asymmetric cryptography

The term “asymmetric” refers to there being two keys, with two different roles. A private key, as its name implies, is meant to be kept private, while the public key can be publicly shared and it won’t affect security (unlike sharing the key in a symmetric cryptosystem). Asymmetric cryptosystems provide the following set of functionality, to encrypt/decrypt and to sign/verify:

keygen() -> (public key, private key) (this function is randomized)

encrypt(plaintext: array<byte>, public key) -> array<byte> (the ciphertext)

decrypt(ciphertext: array<byte>, private key) -> array<byte> (the plaintext)

sign(message: array<byte>, private key) -> array<byte> (the signature)

verify(message: array<byte>, signature: array<byte>, public key) -> bool (whether or not the signature is valid)

The encrypt/decrypt functions have properties similar to their analogs from

symmetric cryptosystems. A message can be encrypted using the public key.

Given the output (ciphertext), it’s hard to determine the input (plaintext)

without the private key. The decrypt function has the obvious correctness

property, that decrypt(encrypt(m, public key), private key) = m.

Symmetric and asymmetric encryption can be compared to physical locks. A symmetric cryptosystem is like a door lock: anyone with the key can lock and unlock it. Asymmetric encryption is like a padlock with a key. You could give the unlocked lock to someone (the public key), they could put a message in a box and then put the lock on, and after that, only you could open the lock because you kept the key (the private key).

The sign/verify functions have the same properties that you would hope physical

signatures would have, in that it’s hard to forge a signature. No matter the

message, without the private key, it’s hard to produce a signature such that

verify(message, signature, public key) returns true. And of course, the

verify function has the obvious correctness property that verify(message, sign(message, private key), public key) = true.

Applications

- PGP email encryption. People can have their public keys posted online (e.g. in a PGP keyserver, or on Keybase). Anyone can send them encrypted email.

- Private messaging. Apps like Signal and Keybase use asymmetric keys to establish private communication channels.

- Signing software. Git can have GPG-signed commits and tags. With a posted public key, anyone can verify the authenticity of downloaded software.

Key distribution

Asymmetric-key cryptography is wonderful, but it has a big challenge of distributing public keys / mapping public keys to real-world identities. There are many solutions to this problem. Signal has one simple solution: trust on first use, and support out-of-band public key exchange (you verify your friends’ “safety numbers” in person). PGP has a different solution, which is web of trust. Keybase has yet another solution of social proof (along with other neat ideas). Each model has its merits; we (the instructors) like Keybase’s model.

Case studies

Password managers

This is an essential tool that everyone should try to use (e.g. KeePassXC). Password managers let you use unique, randomly generated high-entropy passwords for all your websites, and they save all your passwords in one place, encrypted with a symmetric cipher with a key produced from a passphrase using a KDF.

Using a password manager lets you avoid password reuse (so you’re less impacted when websites get compromised), use high-entropy passwords (so you’re less likely to get compromised), and only need to remember a single high-entropy password.

Two-factor authentication

Two-factor authentication (2FA) requires you to use a passphrase (“something you know”) along with a 2FA authenticator (like a YubiKey, “something you have”) in order to protect against stolen passwords and phishing attacks.

Full disk encryption

Keeping your laptop’s entire disk encrypted is an easy way to protect your data in the case that your laptop is stolen. You can use cryptsetup + LUKS on Linux, BitLocker on Windows, or FileVault on macOS. This encrypts the entire disk with a symmetric cipher, with a key protected by a passphrase.

Private messaging

Use Signal or Keybase. End-to-end security is bootstrapped from asymmetric-key encryption. Obtaining your contacts’ public keys is the critical step here. If you want good security, you need to authenticate public keys out-of-band (with Signal or Keybase), or trust social proofs (with Keybase).

SSH

We’ve covered the use of SSH and SSH keys in an earlier lecture. Let’s look at the cryptography aspects of this.

When you run ssh-keygen, it generates an asymmetric keypair, public_key, private_key. This is generated randomly, using entropy provided by the

operating system (collected from hardware events, etc.). The public key is

stored as-is (it’s public, so keeping it a secret is not important), but at

rest, the private key should be encrypted on disk. The ssh-keygen program

prompts the user for a passphrase, and this is fed through a key derivation

function to produce a key, which is then used to encrypt the private key with a

symmetric cipher.

In use, once the server knows the client’s public key (stored in the

.ssh/authorized_keys file), a connecting client can prove its identity using

asymmetric signatures. This is done through

challenge-response.

At a high level, the server picks a random number and sends it to the client.

The client then signs this message and sends the signature back to the server,

which checks the signature against the public key on record. This effectively

proves that the client is in possession of the private key corresponding to the

public key that’s in the server’s .ssh/authorized_keys file, so the server

can allow the client to log in.

Resources

- 2019’s ./missing-lecture security notes: from when this lecture was more focused on security and privacy as a computer user

- Cryptographic Right Answers: answers “what crypto should I use for X?” for many common X.

Exercises

- Entropy.

- Suppose a password is chosen as a concatenation of four lower-case

dictionary words, where each word is selected uniformly at random from a

dictionary of size 100,000. An example of such a password is

correcthorsebatterystaple. How many bits of entropy does this have? - Consider an alternative scheme where a password is chosen as a sequence

of 8 random alphanumeric characters (including both lower-case and

upper-case letters). An example is

rg8Ql34g. How many bits of entropy does this have? - Which is the stronger password?

- Suppose an attacker can try guessing 10,000 passwords per second. On average, how long will it take to break each of the passwords?

- Suppose a password is chosen as a concatenation of four lower-case

dictionary words, where each word is selected uniformly at random from a

dictionary of size 100,000. An example of such a password is

- Cryptographic hash functions. Download a Debian image from a

mirror (e.g. from this Argentinean

mirror.

Cross-check the hash (e.g. using the

sha256sumcommand) with the hash retrieved from the official Debian site (e.g. this file hosted atdebian.org, if you’ve downloaded the linked file from the Argentinean mirror). - Symmetric cryptography. Encrypt a file with AES encryption, using

OpenSSL:

openssl aes-256-cbc -salt -in {input filename} -out {output filename}. Look at the contents usingcatorhexdump. Decrypt it withopenssl aes-256-cbc -d -in {input filename} -out {output filename}and confirm that the contents match the original usingcmp. - Asymmetric cryptography.

- Set up SSH keys on a computer you have access to. Rather than using RSA keys as in the linked tutorial, use more secure ED25519 keys. Make sure your private key is encrypted with a passphrase, so it is protected at rest.

- Set up GPG

- Sign a Git commit with

git commit -Sor create a signed Git tag withgit tag -s. Verify the signature on the commit withgit show --show-signatureor on the tag withgit tag -v.